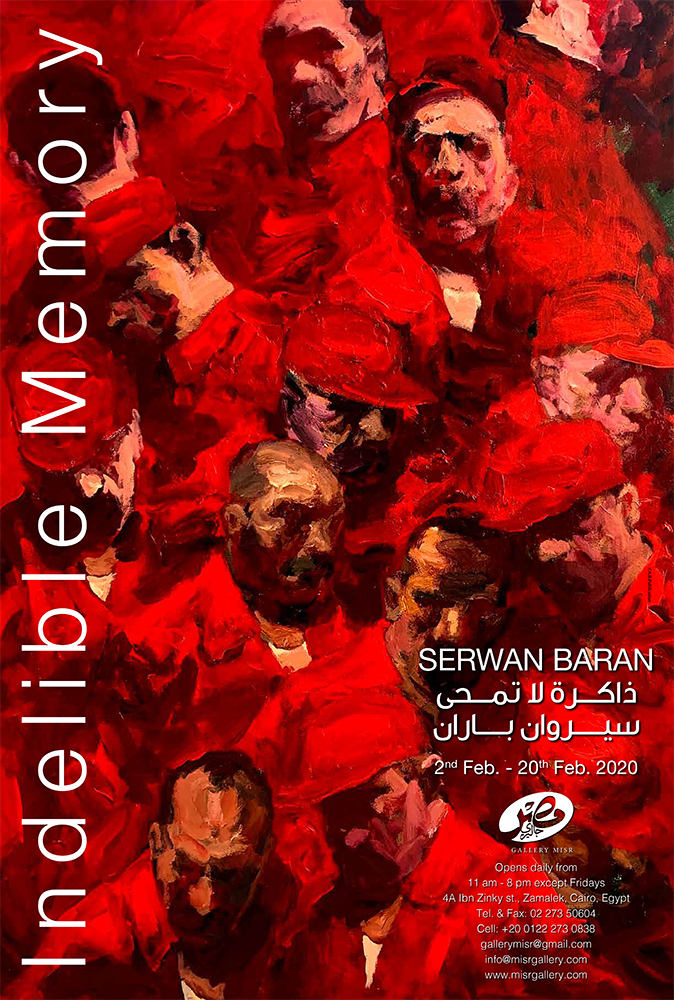

Indelible Memory

Violent brushstrokes revealing acts of oppression and provoking revolutionary spirit

By Mohamed Kamal

I do believe that the native environment and the roots are the chief catalysts for artistic creativity. Perhaps, the artist seeks such Great Environment as a safe haven for his/her individual and unique art. This argument can be successfully applicable to Iraqi artist Serwan Baran. He brilliantly made use of his country’s political and national circumstances for developing his artistic creativity.

Baran was born in Baghdad in 1968, in which the Arab Socialist Baathist Party regained power after ousting President Abdulrahman Aref, the head of the Revolutionary Command Council. Aref was replaced by Ahmed Hasan Al-Bakr, who later assumed the presidency in Iraq. Saddam Hussein was appointed his vice president.

The chaotic circumstances Baran witnessed included partisan and military coups; and an 8-year war between Iraq and Iran from 1980 to 1988. The brutal Iranian-Iraqi war, which claimed the death of about one million people, was followed by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on the 2nd of August in 1990. A US-led coalition of the world major powers launched attack on Iraq in early 1991 to liberate Kuwait. Serwan was a colonel in the Iraqi army; he was an eyewitness of the sufferings and atrocities the Iraqi people were put through by the US’s savage invasion of Iraq.

To tighten its control on the oil-rich Iraq, the US fabricated allegations that its regime possessed nuclear weapons. As a result, the US troops invaded Iraq on the 20th of March, 2003 and removed the Baathist regime of President Saddam Hussein after about 35 years in power, during which prosperity was tainted with blood.

Such drama of human paradoxes must have motivated Serwan’s emotions and intellectual understanding of events around him and their fallouts. For example, initiating his artistic career, the young artist took on impressionism and realism. In this stage, his painting was teeming with figures representing simple and agonized Iraqi people.

Serwan was forced to move to Jordan after the US invasion of his country in 2003. During a 10-year stay in Amman, which is viewed as a bridge of creativity, the Iraqi artist made works to condemn army generals for manipulating the vicious war machine only to increase their trappings of power and medals drenched in the blood of people. His “The Last General” bears strong evidence that army generals are obsessed with wars. The work features a boat carrying the body of a dreamy general with his chest being decorated by a large number of imaginary medals, which, paradoxically, caused his death.

Also, in his acrylic “The Last Meal”, he dramatized the tragedy of Iraqi soldiers, who were massacred as they were having a meal; the green uniform is abbreviated to patches on the rug of merciless and systematic killings; empty dishes and crumbs of bread dispersed in the area invoke the idea of the Last Supper. Serwan’s passion for impressionism is apparent in these two paintings. He came up with graceful brushstrokes to provoke tensions in the space. This technique, he sought for the first time, is apparent in his work “The Motherland”, in which he incorporated sculpture into painting. Serwan exhibited his “Motherland” privately at the 58th edition of Venice Biennale last year. The bird’s-eye-view work voices, through Serwan’s angry brushstrokes, his condemnation to crimes committed by the army generals to increase the number of medals they would be awarded.

On the other hand, Serwan refused to exonerate clergymen from blame in this respect. His work sounds the warning bell that religious people are profiting with cold blood and despicable expediencies by fuelling the flames of sectarianism and tribalism. To strengthen his expression in this area, he cleverly used a variety of artistic techniques and substances, such as clay sculpture, and bronze or polyester casting; painting and drawing; charcoal, oil paints, water colour and acrylic. The surface is canvas or white cardboard, which provokes that sort of interesting tension in Serwan’s mind and emotion. Further, the artist sometimes seeks the help of a friend to ‘deflower’ such an awe-striking atmosphere before he (the artist) intervenes and uses his extraordinary technique to express his idea.

Serwan’s relationship with the dog must have developed in 2003 when the Americans occupied Iraq after a series of military operations and airstrikes from the 20th of March to the 1st of May. He took on the dog as a symbol of ferocious attack. Accordingly, Serwan’s dog is depicted collaborating with the American invaders to terrorise the Iraqi people and sniff for elements of resistance. The Iraqi artist decided to keenly study this animal, which is linked (in his culture) to the ancient civilisations in Egypt, Greece, Persia and Maya.

Serwan’s interest in this animal’s psychology and history increased after moving to Beirut in early 2013. He launched the exhibition “The Dog” in a gallery in the Lebanese capital in 2018 to voice his hatred to repressive regimes and the army generals’ crazy adventures to build a glory—illusive and false as it is—on the bones of soldiers. Serwan’s dog is seen coming across the crazy army generals in “Cycle of Illusion”, an acrylic triptych (200x250cm) he exhibited in the 13th edition of Cairo International Biennale.

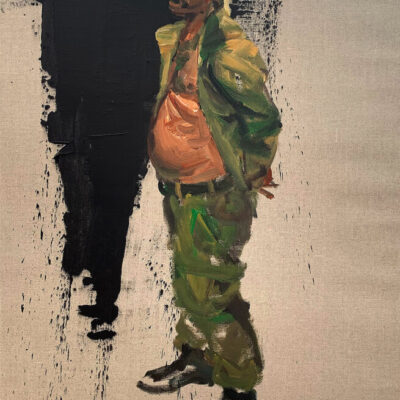

“Cycle of Illusion”, which was on display at the Egyptian Museum of Modern Art, depicts the dog in different positions. First, Serwan’s dog is tied to an army general wearing a black beret and shiny heavy boots. The army general is thrusting his left hand arrogantly in his pocket; his epaulettes are extraordinary heavy. The left side of his face is deliberately dimmed, and so is a halo his head to further signs of callousness and savagery. The general’s bulging mustache also underlines the artist’s vision of the army general’s despicable qualities. The dog is showing its teeth aggressively as if the general ordered it to terrorise someone. A polyhedron in the background helps activate the panic-striking atmosphere in the work. Serwan created a visual and expressionist counterbalance between the motionless geometric form and the mobile representations of the dog and the general.

He used broad brushstrokes to skip details, a technique, which helped him underline the idea of repression and despotism. On the other hand, broad and quick brushstrokes revealed a brilliant assessment of a state of nervousness and tension in the surface to draw the viewer’s attention to the artist’s condemnation to the warlords and merchants of fear. Consistency between the shape and the content underlines Serwan’s credibility.

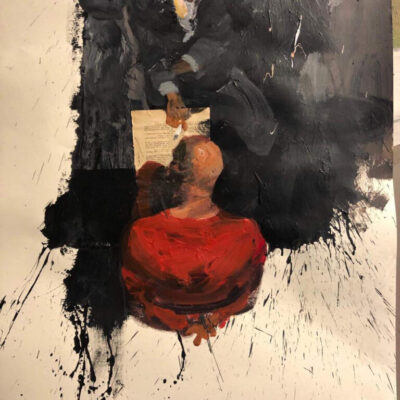

Likewise, Serwan ushers us to the central part of his triptych. Here, the viewer is introduced to a different act of despotism represented by a man wearing black cap and dark glasses; smart suit; white shirt and beautiful necktie; his moustache is elegantly cut. The man holding firmly on his dog tether is on alert. Blood seen on the area between the man and the dog must be referring to a crime being premeditated.

The polyhedron shape visible in the background should indicate that this house-like shape represents fear and panic. Traumatising broad brushstrokes recur in this central part to highlight the artist’s determination to confront acts of repression and oppression. Reaching the climax of the visual drama, Serwan moves us to the left surface where a barefooted prisoner dressed for execution is depicted with his head being covered by a black hood and his hands being tied behind his back. A fierce dog is seen preparing to pounce on him only to increase his fear.

The message delivered by this traumatizing and frightening scene is that the wild dog is symbolically unified with the brutal regime, which is invisible in the work. That is why Serwan came up with more restless and nervous brushstrokes consistent with the horrible atmosphere in the work.

Again, the polyhedron, which is the symbol of brutal authorities arrests the viewer’s attention. A close examination of Serwan’s triptych would reveal that the movement of the beast and the rhythms of perpendicular and horizontal assessments in each part consolidated symbols of despotic regimes. In the meantime, the brushstrokes, which ignore details, motivated the artist’s impressionist technique and highlighted his universal human and political message.

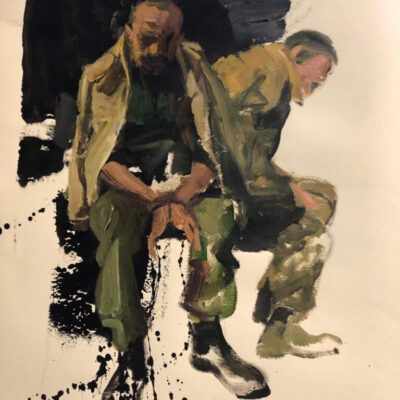

In pursuance of his art, which condemns tyrannies and their criminal acts, Serwan revealed a work (I prefer to name Arrest-1), which features two inmates wearing military uniform; their trousers are loose and their open vests are revealing their bulging bellies. The two prisoners are depicted in two neighbouring surfaces overwhelmed with yellowish atmosphere referring to the armed conflict. Two black patches visible behind each of the two men should remind the viewer of the awe-striking unknown and the sufferings of the inmates, whose dignity and honour, are trampled under the boots of despotic rulers and arrogant occupier.

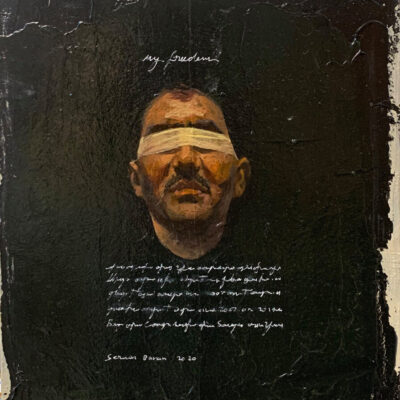

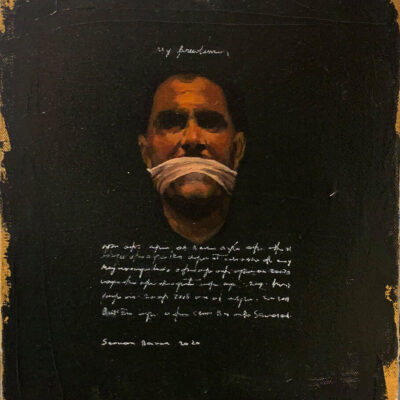

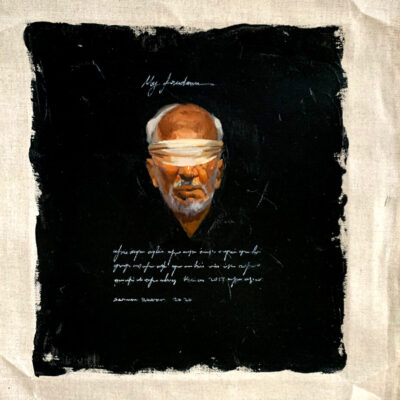

To further their humiliation, the two soldiers are blindfolded by white handkerchiefs. An attentive look at the work would immediately realise the opposing visual rhythm consolidating growing fears and pent-up frustration. Although the two soldiers are blindfolded, their heads are bent down before their colonel. Under Serwan’s rebelling brush lashing the vast yellowish space, the duo appears to be two bullets fired angrily.

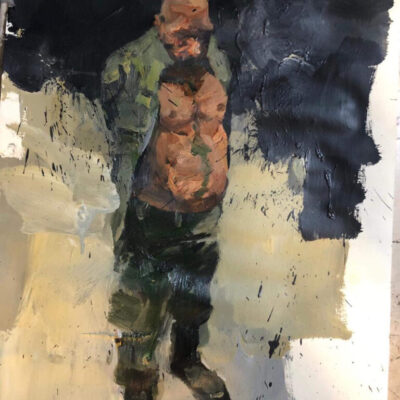

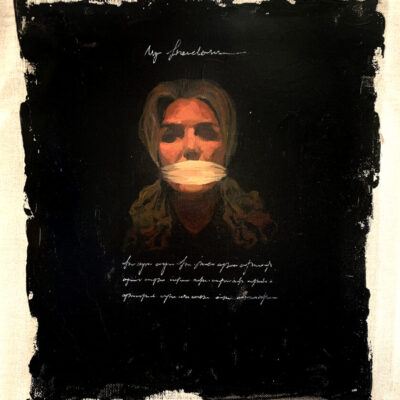

This singular technique recurs in the two works “Arrest 2” and “Arrest 3”, in which he brought a traumatizing embodiment of humiliation and disgrace by painting figures kneeling down with their hands being tied behind their heads.

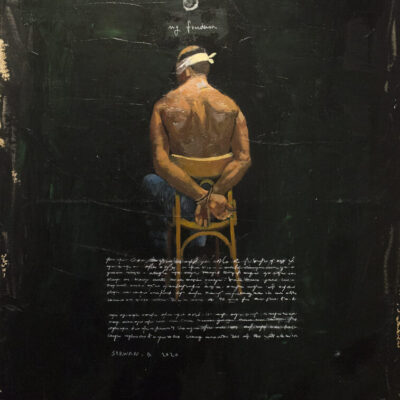

Likewise, the bronze sculpture “Inmate Burnt” features a blindfolded prisoner seated on a chair with his hands being tied from behind; his body is deformed and his head tilting to the left gives the indication that he is dying physically and emotionally. Serwan cleverly delivered his telling message when he left his handprints on the work. He produced a casting of the inmate and the chair to the effect that the solidified mass appears to have been burnt. Like his violent and quick brushstrokes, Serwan’s handprints refer to his overwhelming state of anger during the creation of his work.

If we closely examine this sculpture, we will realise that Serwan’s artistic technique has been shifted from the wholeness to the parts by giving special attention to the images of the victims of oppression, persecution and systematic acts of brutality.

Armed with angry brush and rebelling chisel, the Iraqi artist is giving the clarion call for collective confrontation to resist horrible and criminal acts. His call in this regard is echoing powerfully in paintings overcrowded with figures representing inmates experiencing appalling ordeal in jail. For example, the painting “Jailed in Blue” features a group of prisoners dressed in blue outfit. The dreamy blue overwhelms the space to give an illusion of the softness of repression and the endurable torture in jail. That is why Serwan’s inmates are reduced to a blue rug patterned by red faces revealing simultaneously inner and external emotions. Identification numbers paraded on their vests reinforces the longstanding belief that despotic regimes turn their victims to numbers. Likewise, in his work “Dumb”, Serwan crammed bigger number of his helpless and miserable inmates into the space. Dressed in white robes bearing signs of dust, these victims are looking like a light being trapped between ‘the palms’ of the storm. Once again, the Iraqi artist’s angry and violent brushstrokes produced his clear message. Details are nowhere, otherwise they would dampen the heat of the political and national message he is conveying. Having concerns about the negative impact of details on his message, Serwan’s inmates are not muzzled; signs of agony, humiliation, oppression, disgrace, etc. are clearly visible on their faces and bodies, which must be providing the spark for an imminent revolution.

Serwan’s exhibition “Indelible Memory’ at Gallery Misr is a turning point in his artistic experiment, which has been a bridge to dramatise acts of oppression and simultaneously invoke the revolutionary spirit—by his angry brushstrokes. It must be said that the Iraqi artist has solidified his self with his emotions, mood and psyche through his revolutionary visual state of mind.

SB18