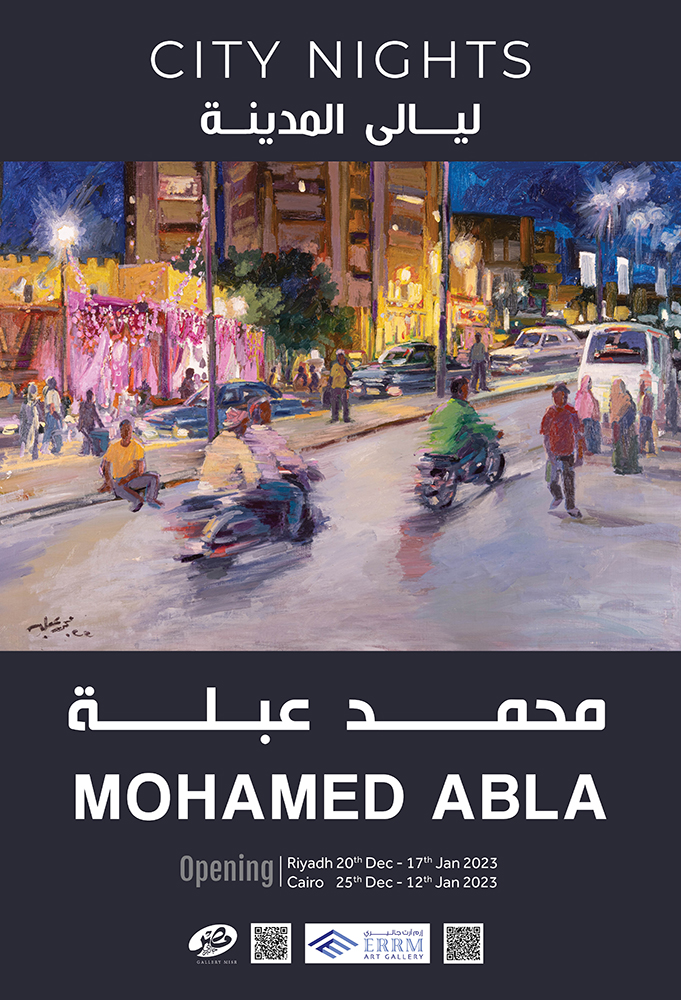

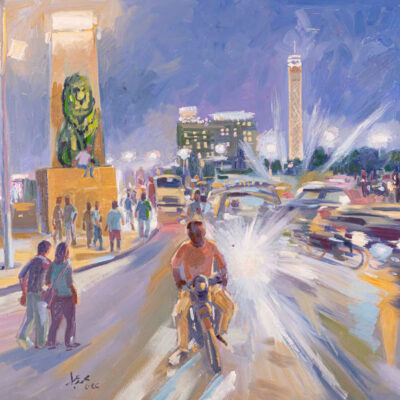

City Nights

Street Moments… Another Life in the City

Gamal Al Qassas

In this exhibition, Mohamed Abla shows the diverse experience he has accumulated in visiual arts over the years to open new windows of understanding and knowledge. He is no longer governed by the construction of form only but rather by human reality and the facts and dreams it entails within this form.

With this perspective, he rekindles his relationship with the city – specifically his beloved Cairo, diving beyond the lines of vision, using its fabric to restore his world and memories and the movement of light and color on the surfaces of his paintings. There are always things that move randomly or in certain proportions, and there are things that move following their survival instinct or under the pressure of fear of this very survival. Abla realizes all this. He also realizes that fear is not isolated in a pure void but rather an issue of life and society and that his beloved rebels against being a prisoner of an abstract, closed form. Wise, insightful, lively and deeply historical, Cairo lies within the heart and conscience. He contemplates the city and rejoices while it is scattered with its sweat and dust in his brush as if it were a visual vibration of his persistent, toiling steps in its streets, alleys and squares, and at the same time as if it were an interpreter of this love. A mass of feelings and dreams interact and grow inside the void, giving the shape a rhythmic pulse. The presence of this rhythm is not limited to the rectangle or square; it extends outside the frame of the image, forming a vivid reflection in the mirrors of reality.

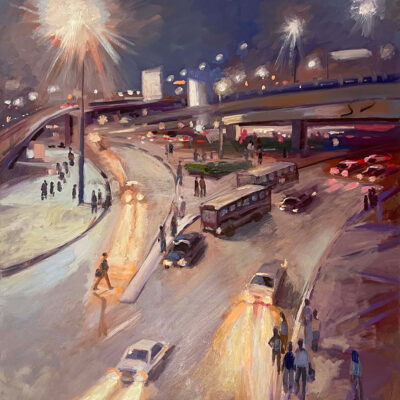

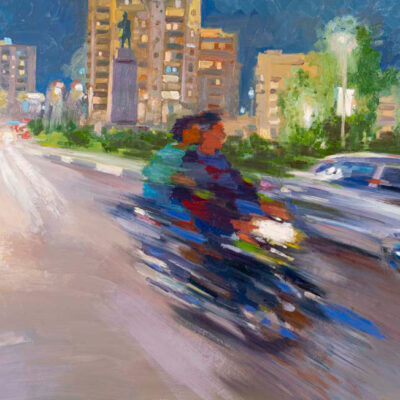

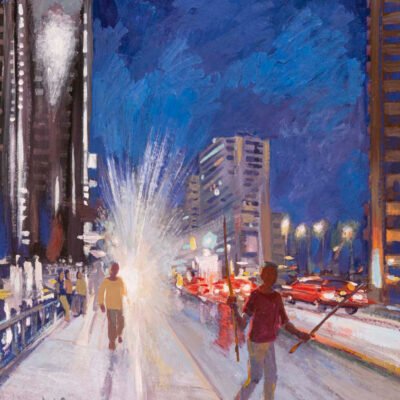

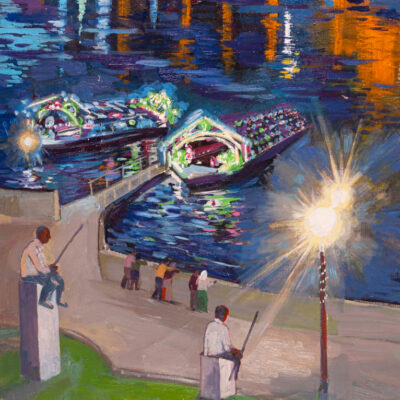

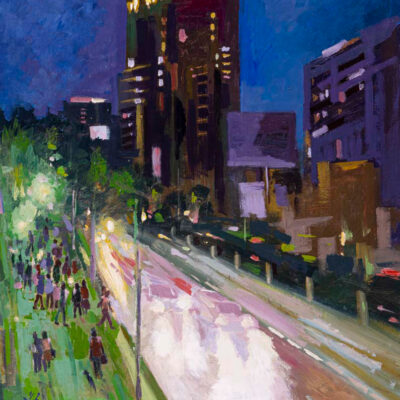

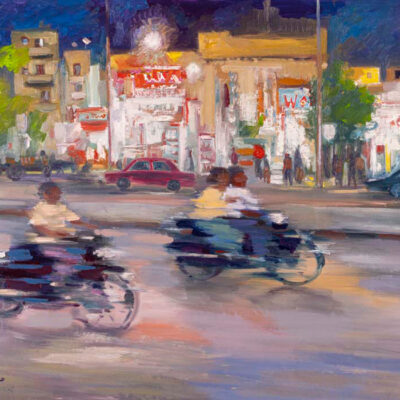

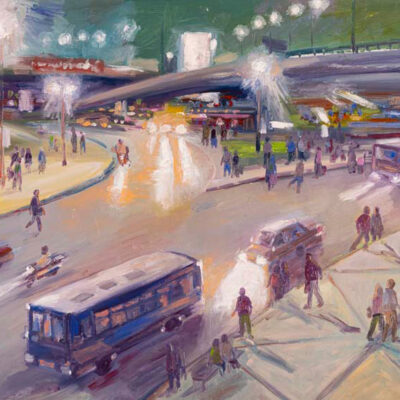

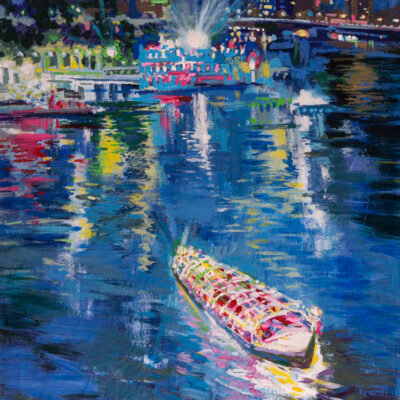

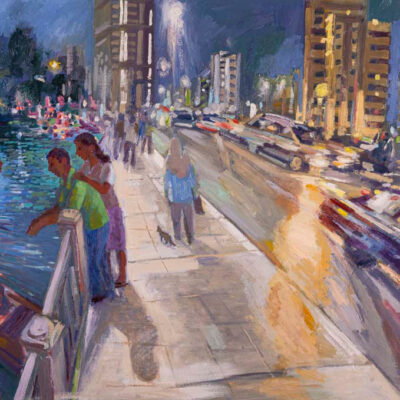

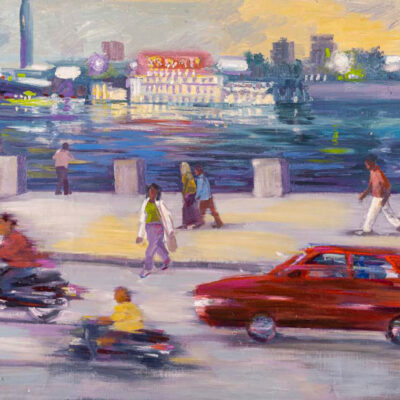

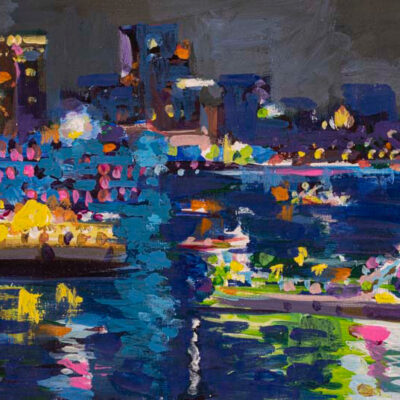

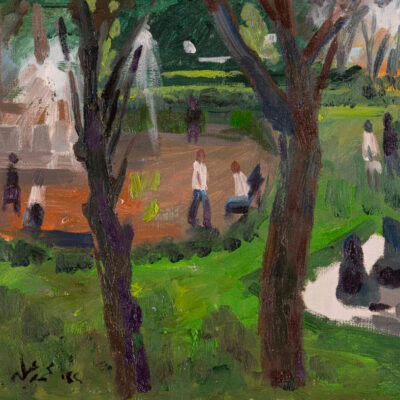

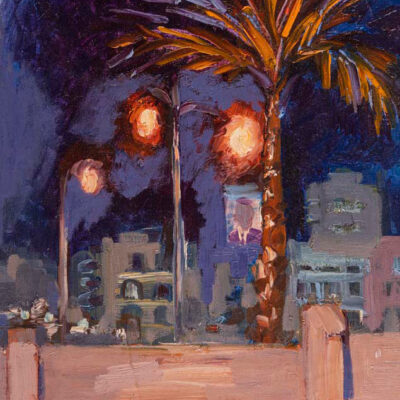

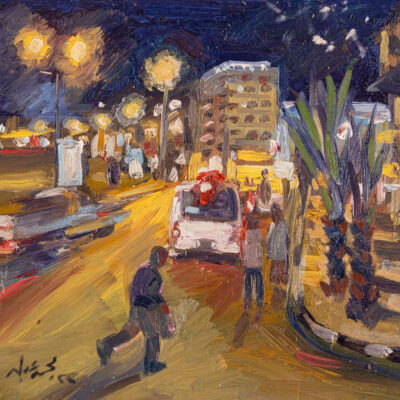

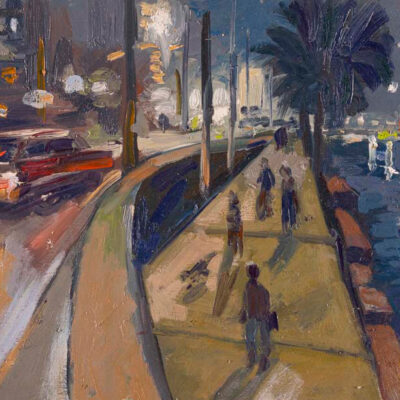

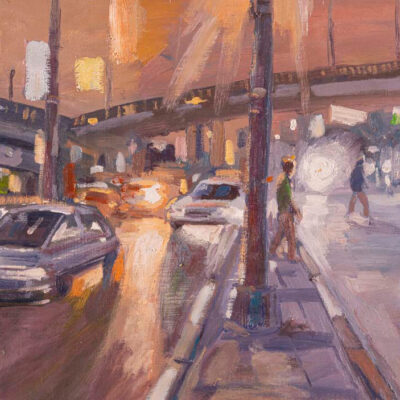

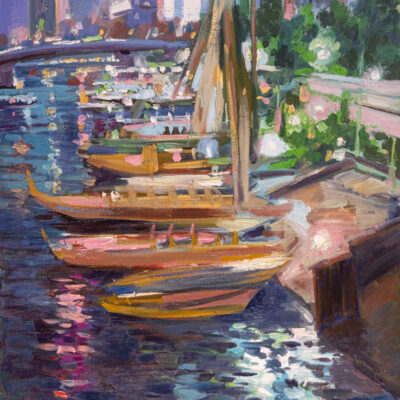

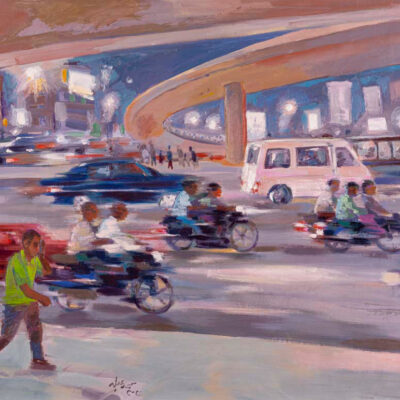

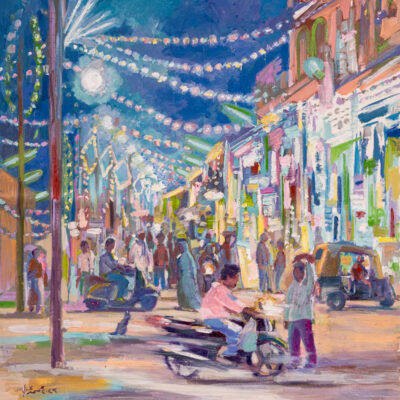

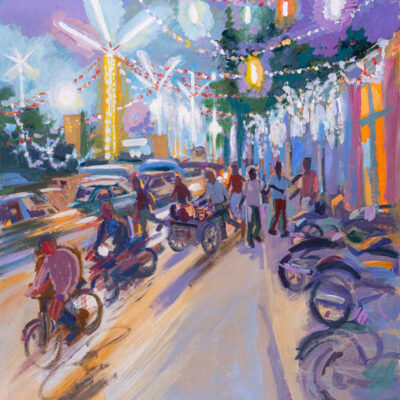

Abla knows that Cairo is a spirited nocturnal city par excellence. Under the curtains of the night and with its stray breezes, the city clears itself from all else, offering a variety of activities reflecting this nocturnal purity in snapshots, scenes and fleeting situations, illustrated by human footsteps and intimate moments. In a previous exhibition called “City Lights,” Abla embarked on an interesting adventure to capture the aesthetics of the artificial night light emanating from the lighting poles in the streets and squares of Cairo, on the banks of the Nile and the noisy night boat carnivals. Through this adventure, he created a new perspective for drawing the city from a very elusive and lively angle. He captured the spirit of the city through shapes and formations that are dominated by the nature of spontaneity and coincidence, sometimes adjoining in contrasting intersections at the level of color, movement and tone, and at others touching from afar, as flashes on trembling surfaces. But the perspective here in this exhibition, and specifically the space of the image, has grown broader, with dynamic movement on the surface of the image and in its texture. This is evident on both the surface and depth levels. The world of vision is no longer based on space as a merely available, direct and visible dimension framed by specific features, landmarks and contexts. Rather, it has become dynamically open to the borders of beginnings and endings. His vision has gone further beyond the place, to the invisible, to what is within; within the characters and forms of tensions, obsessions, feelings and sensations, which involve multiple meanings and connotations, burdened with emotional, social and urban loads.

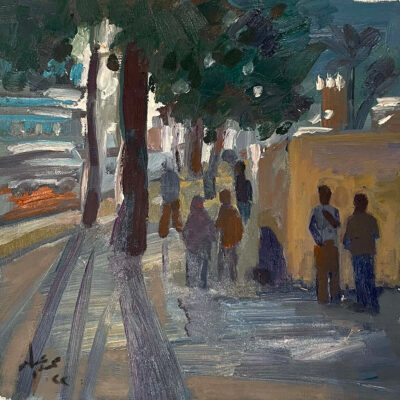

Abla found what he was looking for, using this dimension to capture moments of the streets and squares and their hidden movement in the details of these stolen moments, from the noise of the busy days to the paradoxes and absurdities of reality. He revealed through this dimension another life in the city, shaped in signs and signals and whispered dialogues that flow gently and intermittently under the cloak of night.

This is emphasized by the fact that the exhibition paintings stimulate movement, as the surfaces and shapes automatically exchange roles and move with their warm and calm color layers over the surface of the image with seductive ease. It is remarkable that this movement does not stop at a specific point but rather intersects horizontally and vertically, from the top and bottom and various angles of the image, stimulating a dialogue inhabited by surprise and questions between all the elements of the image. Contrary to the previous exhibition, the dialogue greatly freed itself from the weight of abstraction and the adjacent and inter-relationships between forms and became a non-spoken visual language. The sensory manifestations of this language overflow between the characters and radiate in their camouflaged features and the movement of their bodies with its heaviness and lightness. Here, Abla plays around with the empty space between the conscious and subconscious, the marginalized space that is repressed in the characters’ consciousness, as if it is an echo of an aesthetically elusive void flowing spontaneously between the figures. It is manifested in the anxious looks of the characters and their fleeting joy for managing to steal brief moments from the repercussions of time. The painting becomes a bridge between presence and absence, linking the characters’ past to their present, both in painting and reality.

Abla does not allow his adventure to flow into meaningless experimentation or emptiness; he always invests in building a smooth and attractive aesthetic surface, in which visions condense from multiple angles, getting rid of the stereotypical self-centeredness. In many of his paintings, he turns this adventure into a spiritual energy that the artist uses as a window to the painting and its impact on its surrounding realistic space. The basis of the painting and its vitality is renewed by its ability to spark dialogue both inside and outside in a rising dialectic of steadfastness and movement, and vice versa. This creates an intense visual activity, fromed with the elegance of imagination and efficient insight, and with simple tenderness that gives the viewer a sensory impression that the painting is a wave that renews automatically, in a roaring sea of feelings and sensations. At the same time, it urges them to go beyond the painting, as the light is not reflected only on the painting, it is also reflected on the eye, as well as color, lines, shadows and space.

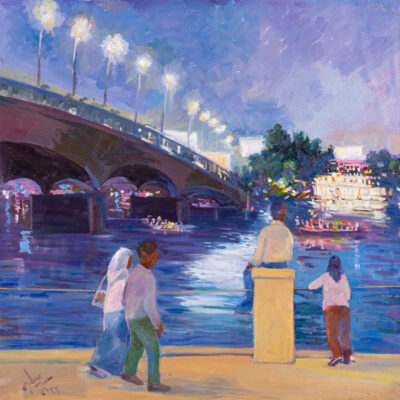

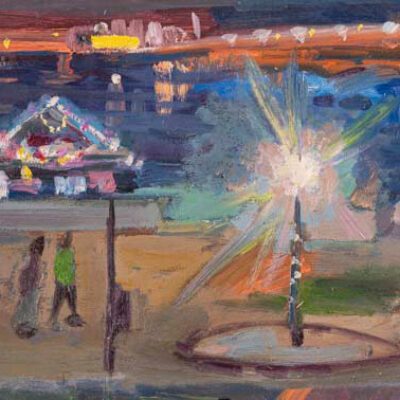

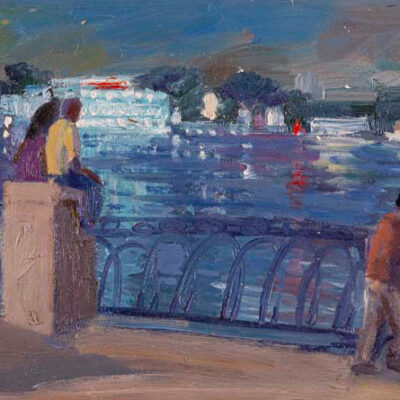

In one of the paintings, a boy and a girl steal a private moment, standing on a bridge, contemplating the Nile flowing beneath them and the scattered fragments of light in the water. The girl puts her hands on the boy’s shoulder, while, from below, ascends a boatman, climbing the mast of his small boat, in a manner that suggests a pleasant conversation where he cheerfully invites them to take a night ride on his boat to enjoy more of their youthful emotional moments. The sense of companionship extends in these moments to include all the elements of the scene on the bridge, so we glimpse a woman strolling with her pet cat, and another mass of people in a state of free-roaming, and in the background, the light shines from the windows of the buildings and from the gray-blue sky.

The juxtapositional structure may seem remarkable in the construction of the scene, but it visually does not repeat itself, but rather seeks what can be called the artistic process, where some objects and elements may resemble each other, yet they reproduce themselves in a new way. In addition, the similarity here is governed by the nature of the city architecturally and aesthetically. It is reflected in the forms and characters, as despite the divergence of points of view between them, they are always united by common concerns and their human suffering, especially in their lifestyles, outlook for the future and pursuit of these stolen moments, as if they are an exceptional ritual that mixes together the clay of the body and the water of the soul.

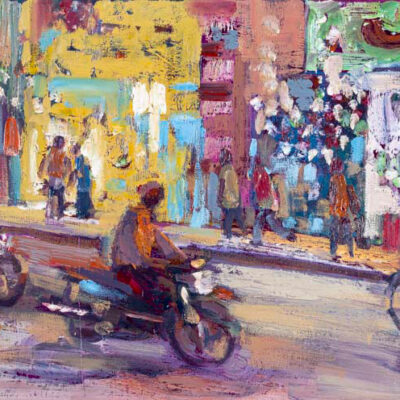

Abla captures this suffering through the dialectic of diversity within the mass. He builds his world not only on the correspondences of light and color with its heavy, oily layer used in the paintings but also on movement, whether in its human individuality filled with a layer of suggestive mystery or in dreamy couples in love, as well as that of more complex groups of people pursuing their dose of daily suffering as if they have become addicted to it to the point of adaptation and submission.

The atmosphere radiates in the paintings with a vigilant eye, following the effects that result from the realistic interactions in the street, in the intersections of bridges, on the banks of the Nile, in the corners of the squares and in the signs of shops and cafes and the neon advertisements scattered all over the city. It is acceptable for this effect to turn into an artistic muse or obsession, but what is most beautiful about the paintings is that this fleeting effect becomes their witness and the first recipient.

One of the manifestations of this vigilant eye is the scene of a young man sitting on the Nile Corniche by himself on a high wall, with his head slightly bowed towards a girl sitting near him, resting one of her arms on the wall. What could he be thinking about in the calmness of this quarrelsome night? Are they two lovers who always keep some distance, igniting longing and nostalgia between them? In the same scene, creating an obvious visual paradox, the distance fades away between a young man and a girl walking slowly exchanging whispers. The painting depicts the young man sitting on top of the wall from behind to widen the horizon of imagination and make him appear drawn by the power of the eyes, senses and mind to a certain point in the fabric of the painting, which may be a spot of light, or a raw movement that has not yet matured, or a shadow of the scattered light from the lighting poles above the bridge, free from feeling the weight of its hard edges and thick structures in the depth of the Nile and its surface decorated with halos of surprising light.

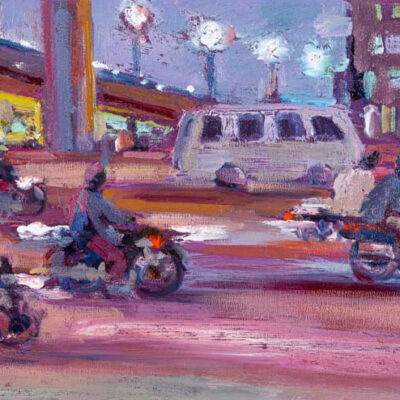

With the tenderness of the scene itself, we see this visual contradiction in an interesting painting. We see a girl riding her motorbike in a state of harmony, and next to her on the same street and under bright showers of light from all angles is a young man riding his motorbike as well. A woman sits behind him embracing him passionately. In another painting, we catch a glimpse of a group of men and women getting ready to take their seats on the bus that stops on the corner of the street.

The movement does not stem from its material similarities in the streets and squares. Rather, Abla captures it in the silent, shallow void, turning it into an echo of a melancholy inner resonance, and a faint ode for places that were abuzz with movement, spaces that have a special history in the collective conscience – places that have become threatened with uprooting and fading away. This melancholy stares at us in one of the large paintings, capturing what remains of the pulse of the houseboats lying on the banks of the Nile in the Zamalek neighbourhood, leaving the audience with a vivid impression of the turmoil that has been raised around them recently, and the threat of taking them away from the Nile’s warm embrace. Abla strips the place, which is a meeting point for the beginning of one of the large bridges that anchors the houseboats, from its elements. He removes any external drivers for movement, and leaves nothing but silence and stillness, with a sharp scar of groaning that penetrates into the fabric of the painting. It is a scene where grief manifests for what can no longer help but embrace its isolation and pain under the gloomy night lights. It is a silent scream for what yesterday stood as a witness to a history that was beating with art and passion for life.

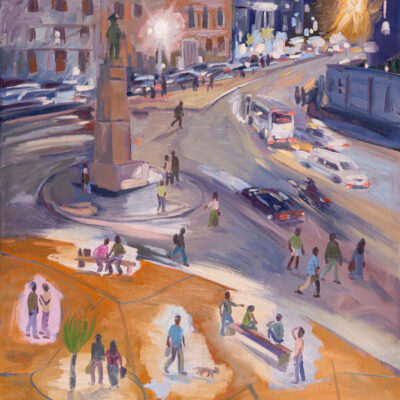

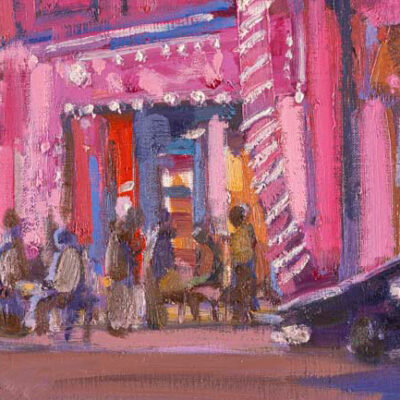

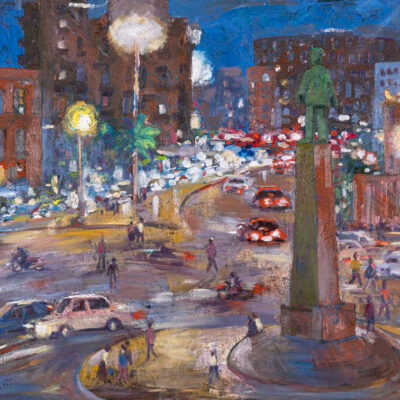

However, the mask of silence is broken. The memory becomes vivid on the surfaces of the shapes, jumping in color leaps and affectionate tufts of light, with a movement tinged with emotion that has a special scent. We see this in two paintings in downtown Cairo, where the scene begins from the statue of Abdel Moneim Riyad in the square carrying his name, then flows with the movement of the street to set the eye on the edges of Tahrir Square. The square appears close and far at the same time, as if it refers to the controversy of memory and dream. The memory here is not far and distant, and neither is the dream. Both of them still have their print on the open space of the square like an open book on the human longing for a more just and safer tomorrow. This spirit is reflected in the two paintings. In one of them, the movement around the statue seems normal, men and women, young men and girls, some of them crossing the street, and some of them sitting on the marble seats next to the statue. In the second, the movement around the statue slows down, and nothing remains but the stream of silence flowing on a white ground saturated with splashes and fragments of yellow, blue, gray, green and matte brown, interrupted by the sounds of speeding vehicles passing in the street while the asphalt floor is scattered with red spots. It is as if the artist’s silenced subconscious exploded in the painting, with its topography restoring the images of the fallen martyrs here and there, chanting in the face of tyrants, “Bread freedom, social equality.”

This slogan, with its simple, spontaneous, revolutionary spirit, almost acts as a summary of Abla’s philosophical and intellectual vision of social burdens. Art, as seen and lived by the son of this movement, is inseparable from reality and the movement of life and its constructive free will. This spirit is reflected in his shapes, with their simplicity and aesthetic and human richness. His eyes are always drawn to the burdens of his country and its people, drawing their nobility, hard work and struggles with pure love.

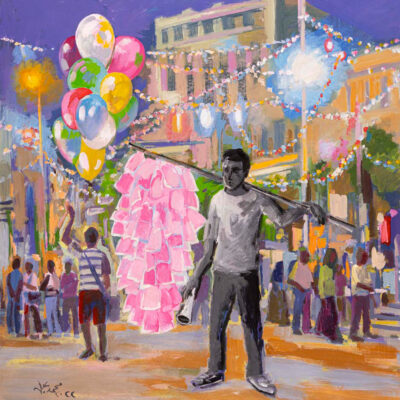

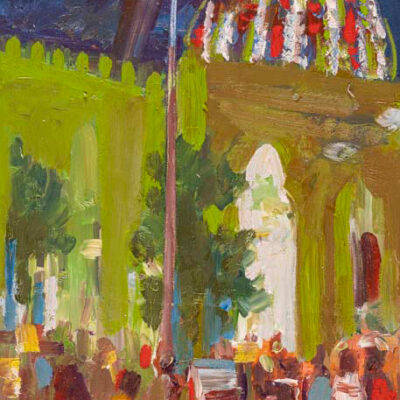

Artistically, we find an echo of all this in the paintings – large, small and medium. There are two lines that form the axis of rhythm in the paintings, distributed softly and seamlessly. The first is intense brightness as a symbol of joy and delight. Here, the colors turn into a child playing with light, lines and shadows, sometimes to the extent of being covered with a carnival tinge, with the sudden appearance of colorful balloons radiating joy and green plants climbing the walls of cafes and streets, as if cleaning the lungs of the city from dust and noise. The second resembles the fading sun during sunset as a symbol of piety and creative asceticism. The artist is a worshiping monk in the temple of art, and at the same time, a skilled hunter for stolen moments. He uses the painting as a filter for such moments, attempting to point his finger to some wisdom that reveals in its shadows what it means to be human, the meaning of survival and eternity; wisdom that stands as the summary of this journey and this dialogue that, when it ends, opens up to other windows in the body of time and space.

Abla deals with place with the same logic of the artistic process. He builds his perceptions of it and in it with a smooth rhythm emanating from the texture of movement, color, light and space. Objects in his paintings are in a constant state of movement. Even at moments of stillness, they overlap and interact, with no intention for direct, symbolic identification and not in search of a specific connotation, or a passing visual effect. Rather, they intensify the vitality of the forms within the painting, drawing them beyond the depths and surfaces the eyes could see, and at the same time giving them a fresh, intimate texture. The act of painting seems like a resonant tone, its rhythm leaps and rises like a musical scale in the strokes of his brush as the affectionate, quarrelsome night light slips into the pores of the surfaces and spaces. This vitality is reflected in its spontaneity in the movement of the characters within the place, with a tinge of nostalgia covering their features, exuding tenderness and fondness for the place, embracing its details and taking refuge in its dust and fragments scattered in the space of the painting, as if it were a shadow of their forgotten and marginalized steps and dreams.

Abla does not have random formations. Even in his extreme moments of experimentation, he always maintains a relationship of fraternity and harmony between abstraction and embodiment, setting his style apart. His experiments with color and material are not purely laboratory but rather to discover a broader extent of the artist’s freedom in dealing with his tools and works and enriching the methods of forming them aesthetically and visually. The painting is not just a test of the artist’s liberation from the power of the material and his ability to adapt it as he likes and desires. Rather, it is an act of freedom. On its surface, his strength and fragility are embodied, along with his ability to break chains and re-establish his freedom and intimate boundaries in the face of time and its stolen anxious moments, footsteps of people, elements and things. Greetings to Mohamed Abla for his ever-renewing adventure, and for this hearty meal of beauty.

Translated by: Sarah El Sebaye

Alexandria II